A vision for Northern California Regional Rail

There are many important rail expansion projects happening and planned in Northern California.

Electrified Caltrain service is set to launch this September, which enables faster, more frequent service to more stops.

Construction for BART to Silicon Valley broke ground in June with service expected to begin in 2036.

Valley Link, a new rail service that’ll operate between Dublin/Pleasanton BART and Mountain House, is set to launch in 2027, with project construction to begin in 2025.

SMART construction to Windsor began earlier this year, with service planned to start in 2025, and eventual plans to expand to Healdsburg and Cloverdale.

Valley Rail will expand ACE and Amtrak San Joaquin passenger rail service with 16 new stations in the San Joaquin Valley, Sacramento, and the Bay Area. The project is expected to be completed by the end of 2027.

Caltrain service (and eventually California High Speed Rail) will extend to the Salesforce Transit Center by the 2030’s, pending full funding of “the Portal” project.

Plans for a 2nd Transbay Crossing are currently being scoped as part of the Link21 Program.

While these various plans for rail expansions are overall good, Northern California lacks a vision for what our rail network can be. Northern California needs a mega-regional rail plan that prioritizes upgrading existing and planned routes into an electrified, frequent, fast, and well-connected network. Aligning capital investments with outcomes such as desired travel times between destinations and facilitating seamless connections between services will be crucial to dramatically increasing transit ridership across the megaregion.

The current state of Northern California’s regional rail network and an envisioned expansion, based on the California State Rail Plan and efforts currently underway.

Why a Mega-Regional Rail Vision and Plan is important

Today, the 21-county Northern California megaregion – which encompasses the greater San Francisco Bay Area, Sacramento area, Northern San Joaquin Valley, and Monterey Bay area – is home to 12.5 million people and the population is expected to reach 16 million by 2050. Decades of land use and transportation policy choices that made driving privately owned cars very easy have led to negative impacts on Californians. Car-dependency eats a significant share of people's incomes, especially for low-income communities. Car-dependency perpetuates long standing socio-economic inequalities, harms our health and environment, exacerbates traffic congestion, and makes addressing our housing crisis with infill development more difficult.

For many people, however, transit is not a viable option as trips can take two to four times longer than driving. Within our megaregion, there are dozens of transit agencies and numerous regional bodies that do various degrees of coordination, but there is no organization responsible and accountable for improving the mega-regional public transit system as a whole. Northern California should pull the pieces together, prioritizing transit coordination and upgrades to regionally significant routes to make transit faster, more reliable, frequent, and better integrated.

Link21 Program should be refocused on advancing an integrated Northern California regional rail network

Right now, Link21 has the broadest scope to connect Northern California’s regional rail network, as envisioned by the California State Rail Plan.

The Link21 “Program Vision” states that:

The Link21 Program and its partners will transform the BART and Regional Rail (including commuter, intercity, and high-speed rail) network in the Northern California Megaregion into a faster, more integrated system that provides a safe, efficient, equitable, and affordable means of travel for all types of trips. [...] With key investments that leverage the existing rail network and increase capacity and system reliability, rail and transit will better meet the travel needs of residents throughout the Megaregion.

Despite this broad reaching vision statement, so far, the majority of Link21’s focus and discourse has focused on the development of a 2nd Transbay Crossing. A major decision will be whether this new crossing will be a wide-gauge track for BART or a standard-gauge track to accommodate regional rail service. In September, we expect that the Link21 team will present its findings on the gauge technology decision to both the BART and Capitol Corridor Joint Powers Authority Board of Directors.

Once a gauge is chosen, decisions on track alignment, new/improved stations, and improved connectivity will be made in advance of an environmental review in late 2025 with construction tentatively scheduled to begin in 2039 and project delivery slated to finish in the 2050s or later.

Link21 has drafted 6 mock-up designs for the 2nd Transbay Crossing. Two of which accommodate BART trains and four which utilize standard gauge for regional rail operators.

While there is merit to consider a 2nd Transbay Crossing in the long run – reducing the negative impacts of transbay service disruptions, creating alternative transbay routes for regional passengers, and helping meet the travel needs of our growing Megaregion – it is clearly no longer one of the region’s highest-priority infrastructure projects given changed travel patterns following the pandemic. In fact, analysis from MTC’s recent draft Transit 2050+ Plan ranks Link21’s cost-benefit performance as low. Furthermore, Link21 is categorized under the “fiscally unconstrained project” section, meaning that more than 3 dozen other capital and operational transit improvement projects will get funding before Link21.

A summary sheet of the rail and ferry network priority projects that the region plans to implement in the near term (2025-2035) and long term (2036-2050), as per MTC’s draft Transit 2050+ Plan.

What the megaregion should prioritize (based on both the Link21 analysis and from the region’s State Rail Plan) is the creation of an integrated, all-day, electrified regional rail network – following many of the steps that Caltrain has started to take. Many of the regional rail services (Capitol Corridor, ACE, and San Joaquins) were traditionally conceived of as ‘commuter’ rail targeted at 9-to-5, white-collar workers. Converting these rail corridors into faster, more frequent service can occur much more quickly, and at a lower cost, than building a second rail crossing, while generating significant new ridership.

In the short- to medium-term, Link21 should refocus its goals on identifying key rail infrastructure upgrades in the broader 21-county megaregion and de-prioritize its efforts on the 2nd Transbay Crossing. While the relative priority of a 2nd Transbay Crossing has changed, the Link21 Program has renewed the momentum and resources going towards regional rail planning. We will need to keep channeling this energy moving forward and craft a network that improves trip times and the rider experience on all regional routes.

Identifying a governance structure to achieve this vision

Achieving an integrated mega-regional rail network suffers from the same challenge as many regional integration opportunities in the Bay Area – there is no entity clearly in charge of bringing about such a vision. A new governance structure needs to be developed to bring about an ambitious vision for regional rail. The State, regional rail providers, and regional planning bodies must work together to clearly identify a governance framework that can move this vision forward and includes all the relevant stakeholders.

Link21 has the broadest regional scope, but its structure does not include all the right stakeholders – with representatives from only BART and Capitol Corridor – nor is it adequately funded or structured to achieve this vision.

Additionally, the Megaregion Working Group may be a structure that can be used as a foundation. It is an existing forum in which the Bay Area, Sacramento, and San Joaquin counties and cities tackle shared transportation challenges, secure discretionary state and federal dollars, and maintenance of long-range Regional Transportation Plans and Sustainable Communities Strategies.

However, the Megaregion Working Group has largely focused on securing funds for capital projects – such as managed/express highway lanes, rail improvements projects, and rail expansions. Transforming the Megaregion Working Group into a body that can achieve these ambitious goals would require reforming their goals and organizational structure, expanding its authority, and greater resources and staffing.

The “Megaregion Dozen” project list are shared priorities amongst MTC, Sacramento Area Council of Governments, and San Joaquin Council of Governments for tackling transportation challenges. (Source: January 2023 Megaregion Working Group Meeting, pages 15 and 16).

The State can also step up and take leadership on the issue. This could mean the creation of a new mega-regional entity with the authority, funding, and broad stakeholder representation to achieve a plan. Or this could be set up through existing agencies, such as Caltrans’ Division of Rail and Mass Transportation.

Case study: Amtrak Capitol Corridor’s South Bay Connect project

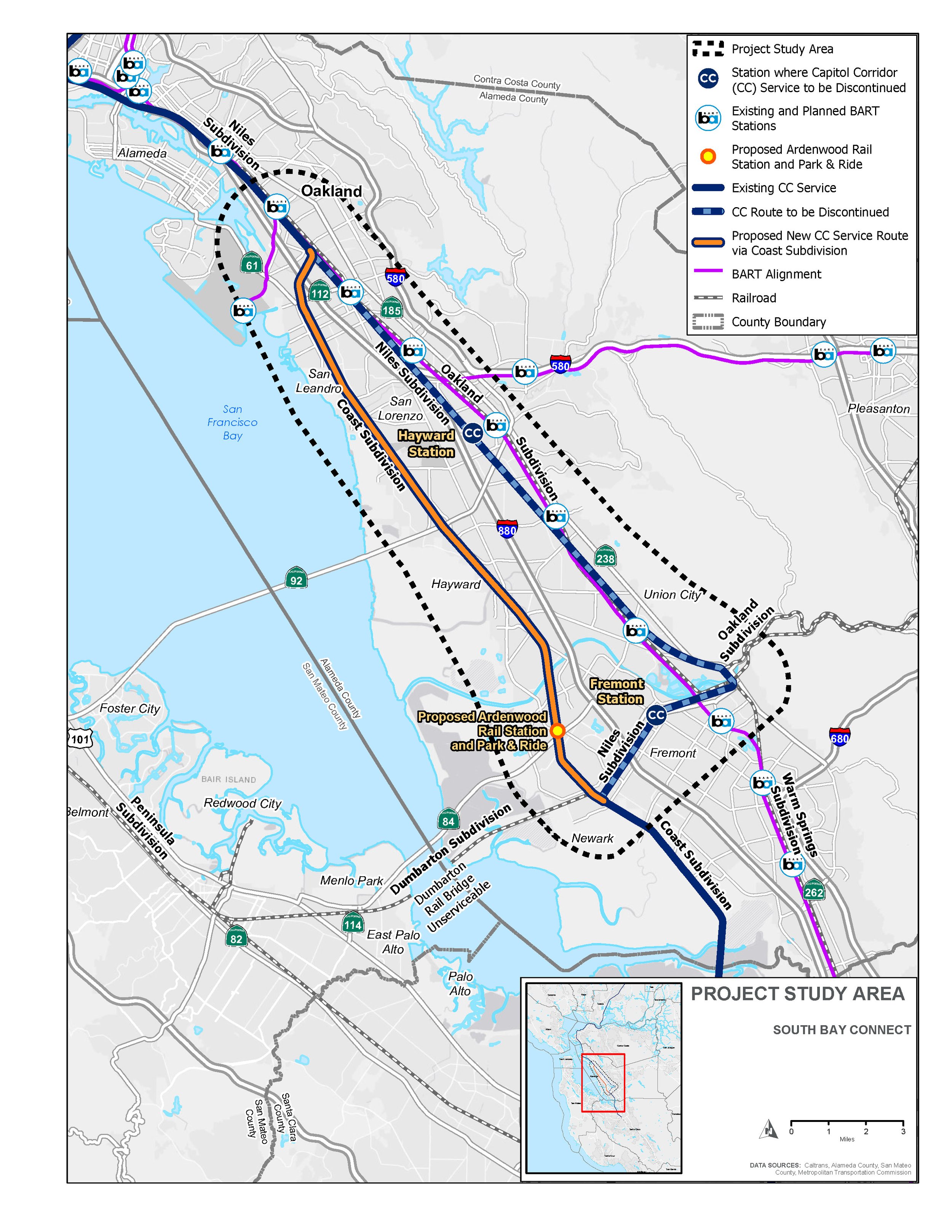

One important example of a project that could advance the goal of an integrated regional rail network is Capitol Corridor’s South Bay Connect Project. The aim of this project is to separate passenger and freight rail between Oakland Coliseum and Newark by relocating Capitol Corridor service to a route west of the current track. This new alignment will decrease travel times by 13 minutes in each direction, improve reliability thanks to less conflicts with freight rail, and add a new Ardenwood Station in Fremont.

This type of major track realignment is the kind of improvement needed to enhance the rider experience on our regional network. However, the draft Environmental Impact Review and other public documents do not mention Capitol Corridor taking steps to proactively upgrade the corridor with overhead electrification, despite the agency’s 2014 Vision Plan Update noting electrification as one of its long-term goals. Electrification would provide a massive improvement for this inter-city corridor, with top speeds of 150 mph that could reduce travel times between Sacramento and Oakland to an hour, and between Oakland to San Jose to half an hour. Having a clearer vision for an integrated regional rail system could help ensure that projects like South Bay Connect are appropriately prioritized and leveraged to advance a long-term vision of integrated, connected rail system.

Conclusion

Northern California already has the foundations for a good regional rail network with numerous rail corridors crisscrossing major urban centers. The planned expansions will create even more options for communities throughout our region to get around via transit. But at this critical juncture where the State and regional leaders are recognizing the need for greater cross-jurisdictional coordination, now is the time for Northern California to develop a clear regional rail vision, and clearly identify a lead entity to guide these efforts.