Funding Seamless Transit (Part 1): Seamless transit is possible with complex funding

Each of Bay Area’s 27 transit agencies have a different funding structure, but this complexity does not need to prevent the agencies from operating as one seamless system.

Funding for public transit in the Bay Area is, on the surface, a complex tangle of sales taxes, regional measures, bridge tolls, state funds, fare revenue, and other sources. Unfortunately, many Bay Area transit agency leaders have suggested that greater integration among the Bay Area’s 27 transit agencies is impossible due to our region’s funding complexity. We at Seamless Bay Area are under no illusions that transit integration will be easy, but our research into the complexities of transit funding management has revealed four key findings:

Public transit finance is complex, but not quite as complex as is often portrayed.

The Bay Area is not unique in this complexity.

This complexity is a challenge to integration, but is not insurmountable. Serious conversations will generate solutions.

The benefits are worth it.

In fact, there are many examples of regions that have complex local funding arrangements but deliver service seamlessly due to the creation of a network manager, which preserves local funding levels — an issue about which Bay Area transit agencies are especially concerned.

In this three-part blog series, we will explain how network managers in other parts of the world manage complicated funding sources, provide an overview of how transit is funded in the Bay Area, and conclude with some thoughts about how a network manager could help reduce the funding complexity in the Bay Area while respecting local fund sources and local levels of service.

We hope these posts provoke questions that can be investigated more deeply in the upcoming MTC-led Network Management Business Case, expected to begin this fall.

Part One: How Does a Network Manager Oversee a Complex Funding Landscape?

The Bay Area has a long and painful history of attempts at transit coordination. While all the bad blood and history that has come before may create political obstacles, it by no means precludes the possibility of creating a network manager — a lead authority that oversees common regional functions of the transit network, such as fare policy, schedule coordination, and branding. Regions much older and more divided than the Bay Area have united their transit systems under network managers with many positive benefits for riders. Managing funding is often the most difficult problem to overcome, but leaders in other regions with network managers have found solutions that meet their local needs.

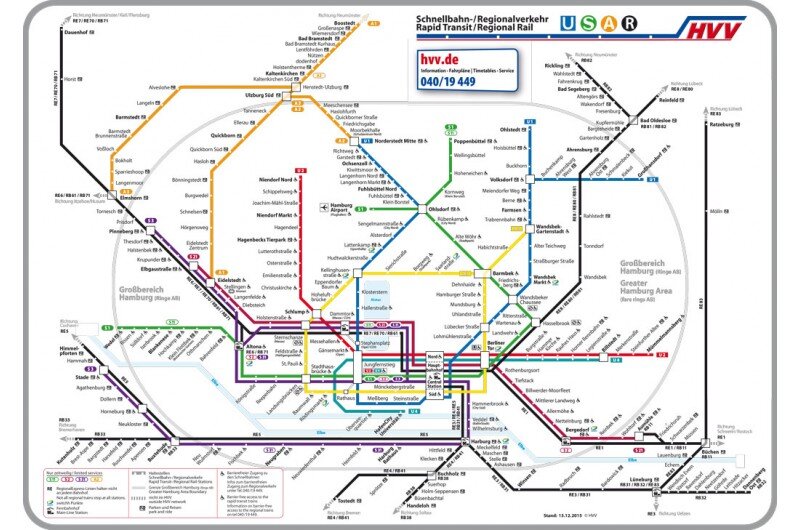

Network map for HVV, the network manager for the Hamburg region, which includes 25 different transit operators.

Learning from Hamburg

One of the first cities to solve this problem was Hamburg, the first city in Germany to establish a network manager (known in German as a Verkehrsverbund). Hamburg created a network manager whose original three members included two municipally-owned agencies and a federally-owned rail agency (this has over time expanded to 25 agencies including a number of private transport companies). The diverse nature of the members basically guaranteed a mix of funding streams similar to the complexity that current Bay Area transit agencies view as a nonstarter for integration.

Reconciling concerns about the equitable distribution of fare revenues by the new network manager (in addition to disagreements about power-sharing and future major infrastructure projects) in Hamburg was a critical part of the 5-year negotiations leading up to its formation, and one of the most contentious. Ultimately, the solution they settled on, which has also been adopted in many other German-speaking regions, included two parts:

Each operator was guaranteed at least the same fare revenue it received before the creation of Hamburg’s network manager. This guaranteed no transit agency would lose money from the change.

The network manager collected all fare revenue and distributed it according to service provided, not according to ridership. This disincentivized transit agencies from competing with each other, while making accession to the network manager attractive to companies who would lose passengers to route consolidations (Krause 2009).

By having a meaningful discussion about the needs of all involved, the agencies that established Hamburg’s network manager created a revenue distribution process that ensured prospective agencies could only benefit from joining the network manager. This revenue distribution process worked so well that it remained unchanged for three decades and was emulated in cities across Germany who established their own network managers.

Network Map for the Rhein-Ruhr region in Germany, which like the Bay Area, is a poly-centric region with many mid-sized cities and funding sources.

Beyond Hamburg, many regions have established network managers with a wide range of parameters and processes, each tailored to their own unique regional needs. Germany’s Rhein-Ruhr region, a polycentric metropolis similar in structure to the Bay Area, succeeded in creating a network manager despite not having a dominant transit agency with a concerted push from local and state politicians and activists (Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr). Zurich, Switzerland took the approach of removing public transport funding responsibilities from municipalities and vesting it in the network manager (2021, Interview of source at ZVV by the author), which now manages 37 agencies. Toronto, Canada, meanwhile, opted to give its network manager a large stream of provincial money to entice the agencies in the region to cooperate while giving it no formal power to coerce them to do so (2021, Interview of former employee at Metrolinx by the author).

Accommodating Regional Priorities

Of course, every region has different needs, and what worked in Hamburg, Rhein-Ruhr, Zurich, or Toronto isn’t guaranteed to work in the Bay Area. However, the governance and financing structures of network managers can adapt to address regional needs, provided regional leaders are willing to engage in a meaningful discussion about how to make a network manager work. There is no required recipe — leaders can and should tailor it to meet both local and regional needs.

An upcoming business case on network management has been identified as a next step of the region’s recently adopted Transformation Action Plan. That study will allow for a detailed discussion of how local funding can support shared goals and a seamless system, and the estimation of the amount of new funds that will be needed to fund integration. Agencies and advocates should prioritize raising new regional sources of funding, such as through a future regional ballot measure, which can help provide the Hamburg-style ‘guarantee’ that agencies will not lose money as a result of switching to a new system of fare revenue allocation.

Read on to Part Two of our blog series, which will dissect the various funding sources in the Bay Area.

References

Krause, Reinhard. (2009). Der Hamburger Verkehrsverbund von seiner Gründung 1965 bis heute. Hamburg, Norderstedt: Satz, Herstellung und Verlag.

Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr. (2021, May 14). 40 Jahre VRR. Retrieved from VRR: https://www.vrr.de/de/magazin/40-jahre-vrr-geschichten-aus-vier-jahrzehnten-oepnv/